Hearing aid + accessory + smartphone app = a ‘synching’ feeling? Marshall Chasin explains why patients might be losing the rhythm.

The historical literature (at least going back to some of the classic texts in the 1960s) is full of recommendations to improve the environment to optimise lip-reading cues for hard of hearing people. Of course, back then, one needed to be relatively close to obtain these visual cues.

A few lines of algebra will show that for roughly every 1/3 metre (or 1.1 foot) of distance, there will be a one millisecond (msec) delay between visual and auditory cues. At four or five metres - a realistic distance for the upper limit of lip reading - there will be 12-15 msec of delay, and this is quite reasonable. We are relatively immune to such short delays and a 12-15 msec mismatch between the facial cues and the perception of the sound poses no real issue. For distances farther than five or more metres, lip reading can be problematic and other means of speech transmission need to step up to the plate. In other words, lip reading and facial cues are self-limiting. By the time a speaker is far enough away, despite some potential time delay, lip and facial cues are of no real significance.

Historically, there were not many options short of hearing aids which, in the 1960s, 1970s and for much of the 1980s, used rudimentary linear peak clipping type A amplifiers. Assistive listening devices such as FM systems, infrared systems and inductive loop systems were introduced in clinical practice to improve communication. However, for larger distances between the speaker and listener, visual and facial cues were not effective, or, in other words, visual cues were not considered a ‘distraction’.

Visual cues as a distraction

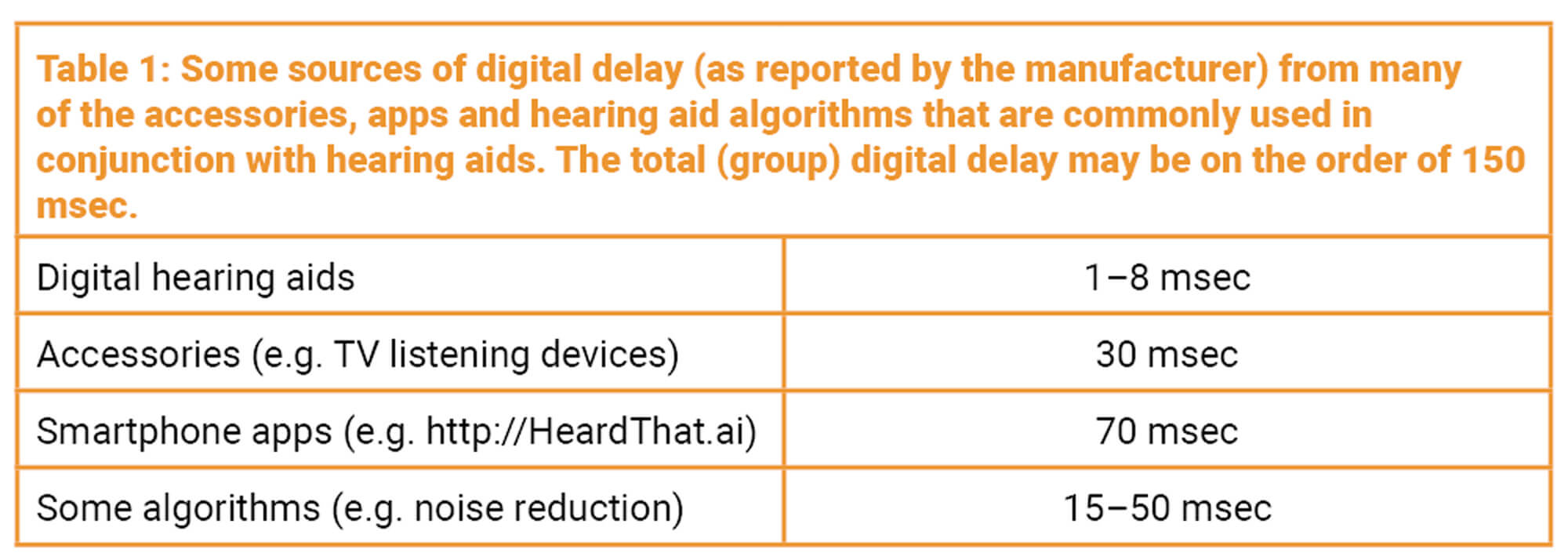

But this ‘distraction’ is now rearing its ugly head once again with modern hearing aid algorithms such as noise reduction, the use of some forms of AI, some smartphone apps, and the use of some accessories (Bluetooth or otherwise) where the digital delay can be on the order of 50-80 msec, and group digital delays can be far in excess of 100 msec. These algorithms and accessories can be used even if the hard-of-hearing listener is only one to two metres away. In scenarios such as this, lip reading and visual cues can be significantly out of ‘synch’ with each other, leading to a ‘distraction’ and a potential degradation of communication. And to further complicate things, depending on the hearing aid technology used - bank of detection filters or FFT - many of the sources have differing delays as a function of frequency. It is almost as if a hard-of-hearing person may need to close their eyes when these algorithms, accessories and smartphone apps are being used. Table 1 shows some expected digital delays for several devices, as reported by the manufacturer.